Why we need 'crazy' ideas for new city parks

Wendy Walls,University of Melbourne

Two seemingly unrelated but important things happened in Melbourne last week. One was a memorial service for David Yencken AO; the other was the exhibition opening of the Future Park Design Ideas Competition. The connection between the two is that both gave us radical ideas for Melbourne’s open space.

David Yencken was a visionary man who had a profound impact on Victoria and Melbourne. He was responsible, among many things, for the transformation of Southbank and co-founding Merchant Builders. But one of his wildest ideas was the 1985 Greening of Swanston Street, when vehicle traffic was closed and a weekend street party was held right in the middle of Melbourne.

As the secretary (chief executive) of the Ministry for Planning and Environment, Yencken had been charged with changing perceptions of the city by rethinking its public spaces. At a time before pop-up parks and guerrilla gardening, his radical idea demonstrated what was possible for the inner city and sowed the seed of the idea of closing Swanston Street to traffic.

The project was not without controversy – it was costly and came in for political criticism as a stunt. But looking back to a time when inner Melbourne was underutilised and dominated by traffic, we can see how that radical idea sparked the imagination about what was possible for the city centre.

Future Park fires imaginations and debate

This is just what the Future Park competition needs to achieve. The open competition held by the University of Melbourne and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects has attracted global interest, with 123 entries from 20 countries.

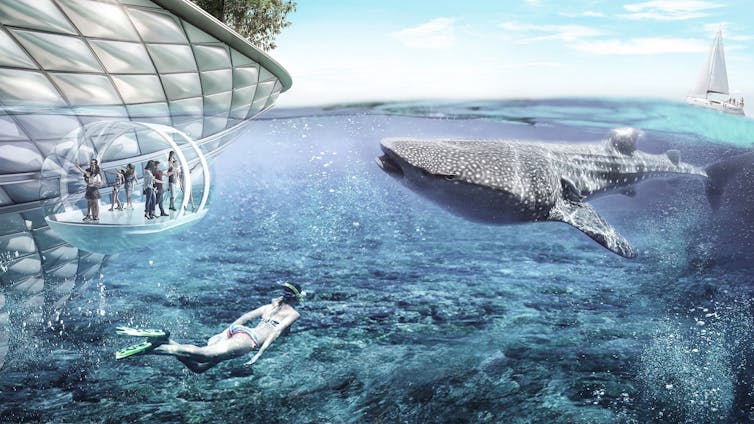

The brief was simple but provocative. Designers were to find space within 10 kilometres of the city centre and design a future park that responds to the challenges of Melbourne today. The design responses from the 31 shortlisted entries ranged from manufactured lagoons to urban wildlife corridors and street transformation parks that Yencken would be proud of.

The first wave of media coverage on the competition inspired a range of public comments about Melbourne’s open space. For example, from the online comments in The Age:

Royal Park is a massive area of underutilised space. Driving down Elliott Av it’s just an open wasteland. Grassland and scattered gum trees does not make a welcoming “park”.

How about bulldozing the eyesore known as Federation Square and putting a park in its place?

These designs forget to include the things that make it a Melbourne park, graffiti, vandalism, weeds and the homeless.

Architects and landscapers rarely, if ever, have a grasp on what will work for people … they are too busy trying to be creative, and not busy enough trying to make people happy.

What the public comments show us is that there is no single or obvious solution to our parks and public spaces. Some people like it busy, some people like the quiet. Some want European trees and others desire native plantings. It’s complicated, and each of these opinions make valid points.

Just like Yencken’s Greening of Swanston, there will always be debate about what makes good public space. And that is exactly why we need more radical ideas – some might call them “crazy” – for our cities.

We know the future of our cities will be complicated. Like it or not, there will be more people, a changing climate and increasing pressure on infrastructure and services.

Wicked problems call for radical thinking

These messy issues are often described as wicked problems. Popular in public policy and management, the term is used to explain problems with debatable cause and effect. Critically, the lack of agreement about wicked problems produces conflicting goals towards resolution.

Obviously, we need science, governance and planning, but finding solutions to wicked problems will also require creativity and collaboration. We need debate and we need ideas that can expand our imagination about what our cities can be. This is why it is so important that the competition entries for the Future Park explore new and outrageous possibilities.

Ideas throughout the shortlisted entries include plans for a new NBN: the National Biodiversity Network, which creates ecological corridors across the country. Others propose transforming schools into parkland; parks designed for bees; designs that return darkness to our urban landscapes; and sculpting new islands as rising sea levels engulf our coastline.

As design solutions, these ideas reflect the challenges of our world today. While many of these schemes are technically, socially or economically unfeasible, they remind us of the power of thinking outside of the box. Importantly, the competition format puts all of these ideas together in one place for us to think about and discuss.

In Australia, we have a limited culture of “open design competitions” for either built projects or speculative solutions. But design competitions provide opportunities for new voices and discovering unexpected solutions within these wild ideas.

Radical ideas are important and so is having the freedom to voice them. Especially as a way of expanding the discussions we need to have about the challenging future.

The Future Park competition winners will be announced on Friday, October 11, at the 2019 International Festival of Landscape Architecture in Melbourne. The Future Park exhibition is at Dulux Gallery, Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne, from October 4 to November 1.

Wendy Walls, Lecturer in Landscape Architecture, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jobs Just For You, The Planning Professional

Our weekly or daily email bulletins are guaranteed to contain only fresh employment opportunities