Planning laws protect people. A poorly regulated rush to boost housing supply will cost us all

Patrick Harris, UNSW Sydney and Edgar Liu, UNSW SydneyThe housing crisis is firmly on the Australian policy agenda. Governments see a rapid increase in supply as the main solution.

The importance of supply is not disputed. But more housing alone isn’t enough: new housing must be provided in ways that do not widen the gap between the “haves and the have-nots”.

Our recent research in Sydney, for instance, shows how the planning system already overlooks what is needed to make the city equitable and liveable. Planning decisions contradict or ignore guidelines and checklists that are meant to help ensure communities are healthy and sustainable.

The rush to build new housing risks creating even more inequitable cities.

Poorly regulated housing development often means services and infrastructure such as public transport or schools are added later. This ends up costing both governments and households. And it costs us more than dollars to fix the long-term problems that come with inequity.

Only housing “done well” – quality, affordable and accessible housing – will truly solve the housing crisis.

Beware the wrong kinds of planning reform

The federal government’s new housing plan aims to put A$3 billion on the table for states and territories to build more housing.

State governments like those in New South Wales and Victoria have now taken steps to speed up the supply of more homes.

While that sounds like good policy, this approach extends decades of short-sightedness that overlooks what matters most for cities: its people.

The NSW government wants to “loosen the screws” on planning regulations so developers can build more housing. Worryingly, it admits wrongdoers may take advantage. The Victorian government unveiled plans on Wednesday to fast-track big housing developments.

Such short-sighted policies risk poorly planned neighbourhoods and poorly built housing.

There’s plenty of evidence for the need to reform the NSW land-use planning system. Simply freeing up housing supply is not enough. Planning systems need to do the job of ensuring new housing supports the city and the wellbeing of all residents.

How land-use planning fails Sydney’s people

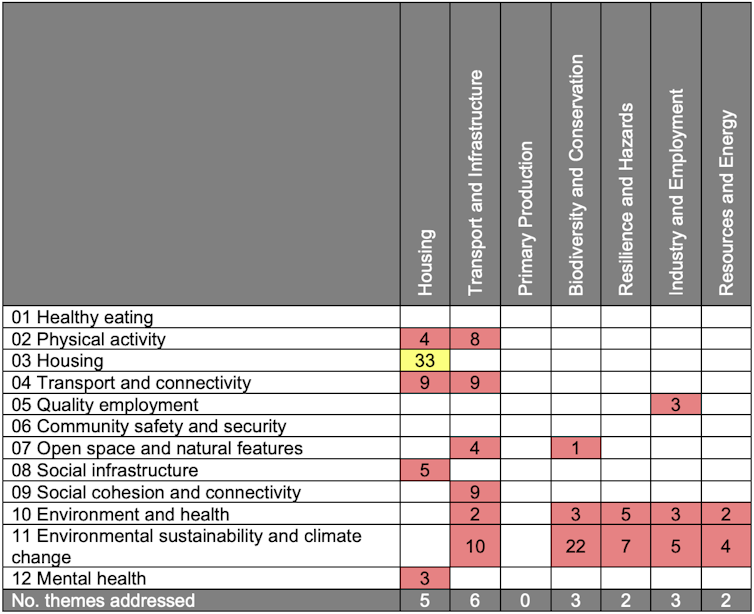

We reviewed NSW’s two main land-use planning mechanisms: State Environmental Planning Policies (SEPPs) and Local Environmental Plans (LEPs). We assessed the ways they help promote the building of safe, liveable neighbourhoods.

We compared these policies against the NSW government’s own Healthy Built Environment Checklist on how to do it well. We found this checklist to be one of the best guides in the world for how cities can enhance human health and wellbeing.

The checklist sets out 11 principles covering topics that the planning system should use to guide development. We added a 12th best-practice theme to highlight the growing importance of safeguarding mental health.

We counted the number of clauses within each policy and plan that corresponded to each of the 12 themes. We used a traffic-light system (shown below) to highlight whether and how these clauses considered, mentioned and/or addressed issues relating to equity.

Because SEPPs are (generally) applicable to the whole state, we found their focus was more thematic and focused on broader issues such as “resilience”. Most only corresponded to a small number of the best-practice themes as show below.

The proposed but-never-adopted Design and Place SEPP was the most likely to have provided any equity guidance.

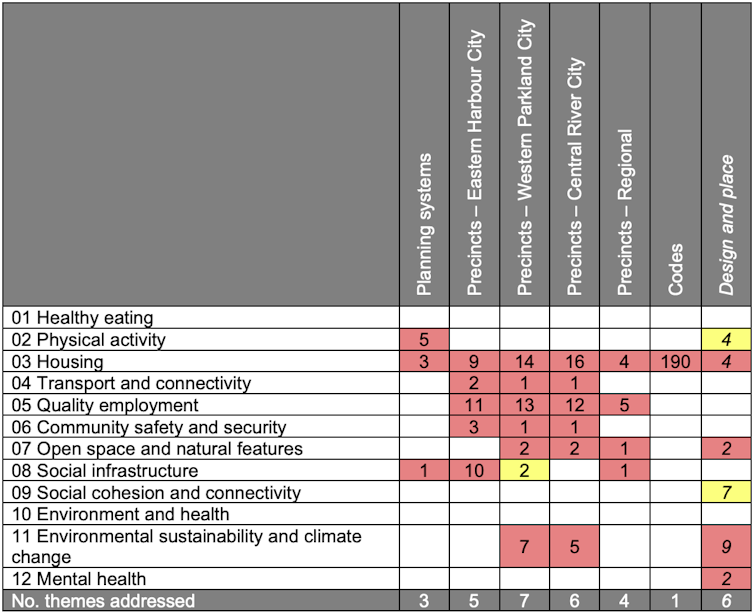

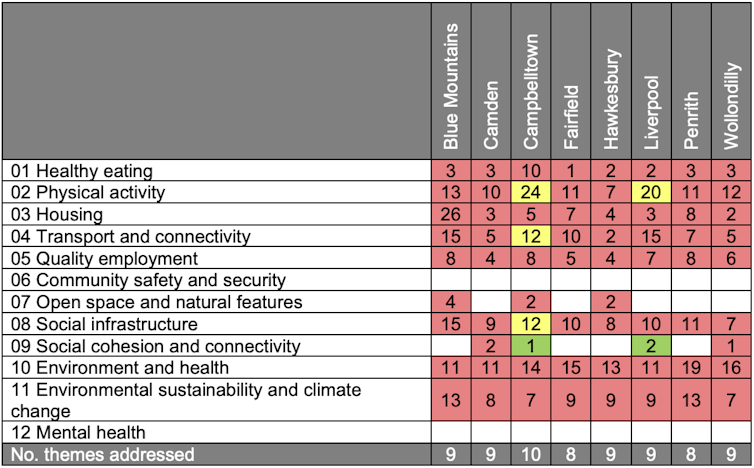

In contrast, LEPs are by design more focused on specific local government areas and need to more comprehensively guide local land use. Most included clauses that aligned with the healthy planning themes.

Nevertheless, as the mostly red coding shows, few of these land-use planning mechanisms considered the known ways to promote equity in any notable ways.

At the local level, only two of the eight LEPs we looked at really paid equity any attention.

Quick fixes risk making things worse

Short-term fixes for the housing crisis create a big risk of even worse outcomes for communities.

“Unleashing” housing supply in cities like Sydney and Melbourne, without reforming narrowly focused planning mechanisms, will increase inequities between the haves and have-nots. The result is likely to be more spending in future — by governments and affected households — to deal with the consequences.

We know how to create great suburbs and cities. Indeed, the NSW government should heed its own policy advice when changing the planning system if cities like Sydney are to remain quality places to live.

Planning must have a local focus

We need to refocus planning strategies on who they are meant to serve — the people and their communities. Thinking locally must be part of the package.

Councils in south-western Sydney, for instance, are partnering local health districts to develop innovative health-focused planning and urban design. Similarly, the Western Sydney Health Alliance is supporting innovation, including our research, to place public health at the centre of delivering infrastructure for the region.

Boosting housing supply by targeting local councils’ roles and responsibilities, as both NSW and Victoria are doing, risks worse, not better, outcomes.

Planning systems need to regulate and be responsive locally for housing to be “done well” and avoid the costs of inequity that come with a blinkered focus on housing supply.![]()

Patrick Harris, Senior Research Fellow, Acting Director, CHETRE, UNSW Sydney and Edgar Liu, Senior Research Fellow, SPHERE's Sustainability Platform / City Futures Research Centre, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jobs Just For You, The Planning Professional

Our weekly or daily email bulletins are guaranteed to contain only fresh employment opportunities